Turning off the highway, we drove up and down an isolated road trying to find the Heart Mountain Interpretative Center. The land was flat and unremarkable. The sun beat down on the parched earth. It really felt like the middle of nowhere. I can imagine that was exactly how the Japanese-Americans who arrived at the Heart Mountain Japanese internment camp in 1942 would have felt.

We eventually located the black barrack style building which looked like nothing special. We had repeatedly overlooked it as we were driving. Although intentionally bleak and uninviting from the outside, the Heart Mountain interpretive centre is informative and captivating.

Contents

The History of Japanese Immigration to the United States

Japanese immigration to the United States began in 1868 when workers were imported for the sugar cane plantations in Hawaii. The Japanese immigrants joined previous Chinese and Portuguese workers. As the last of the immigrants, the Japanese were at the bottom of the totem pole. Working as field hands, the Japanese worked 10-12 hours a day in gruelling conditions. The Japanese became a tight-knit community because the plantation owners segregated their workers by ethnicity.

Initially, many Japanese immigrants came with the hopes of making their fortune and returning home. In 1868, as part of Emperor Meiji’s modernisation plans for feudal Japan, he disbanded the prestigious samurai class and cut off their pensions. At the time, Japan had 1.9 million samurai. Suddenly lots of able-bodied men were left without any source of livelihood. At the same time, Emperor Meiji also relaxed the rules on his subjects leaving the country. By 1890, over 1200 Japanese had made the journey to Hawaii.

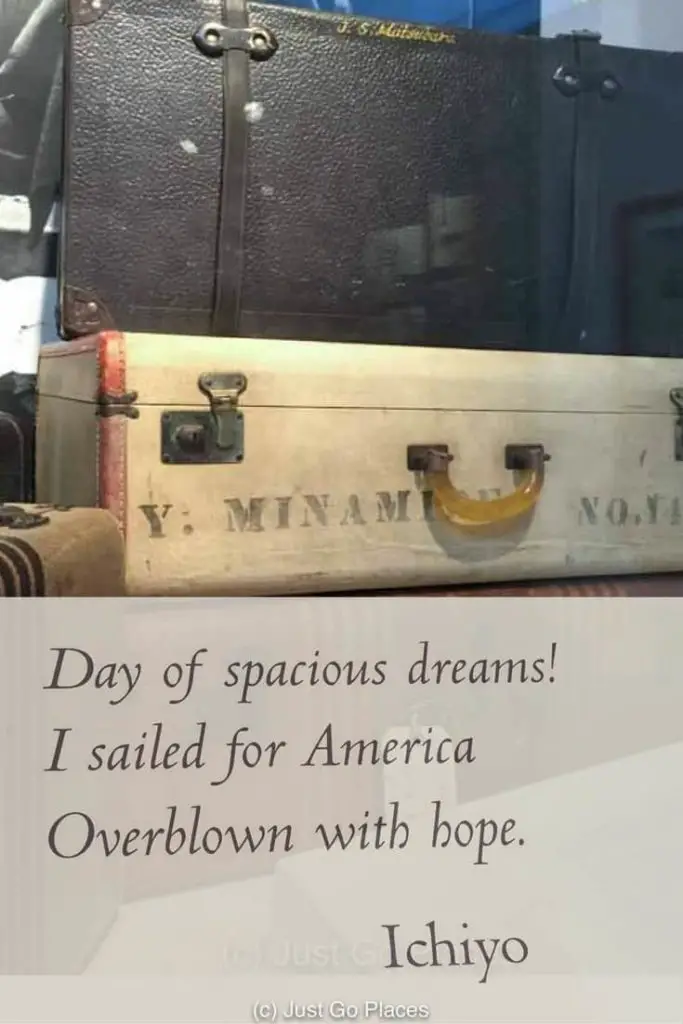

Like other immigrants to the USA, Japanese-Americans came with their hopes and dreams for a better future.

Japanese immigration increased after the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 lead to the prohibition of Chinese labourers. From the Hawaiian plantations, eventually the Japanese moved onto mainland USA to work on railroads, farms, fishing boats, oil fields and mines. Despite heavy racism, some of the Japanese owned their own businesses or farms. For example, the E.D. Hashimoto Company established by a Japanese immigrant in Salt Lake city provided railroad labor to the Western Pacific Railroad.

The first generation (issei) who were Japan-born had never been allowed to become citizens. Under American law at the time, only people of European and African descent could become naturalised citizens. (Japan-born people could not become naturalised citizens until 1952.) By 1940, the nisei (second generation) of Japanese-Americans were integrated into American society and even had children of their own, the sansei (third generation).

Why were Japanese-Americans Forced into Relocation Camps?

President Franklin Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 in February of 1942 as a result of the racism and hysteria prompted by the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour. The attack on Pearl Harbour marked the American entry into World War II. This law lead to the forcible internment of tens of thousands of Japanese Americans living on the West Coast of the USA onto 10 relocation camps. Like the Heart Mountain internment camp, these camps were located effectively in the middle of nowhere USA.

The Japanese-Americans were seen as a threat to national security because of the fear they could be conspiring with the enemy. The sign below was put on a store owned by a Japanese American born in California and educated at the University of California Berkeley. He still felt the need to publicly state his loyalties.

Japanese Americans were given one week to report to the collection centres which would send them onwards to the interment centres. Their lives were uprooted and they didn’t have time to sell off their businesses or dispose of assets. Many people left their personal possessions behind which were quickly stolen by remaining locals.

The Visitor’s Center has a movie by Academy-Award winner Steven Okazaki entitled “All We Could Carry” which is a really good introduction to the rest of the Heart Mountain Interpretive Center. The film title is a reference to what each person could bring with them when they left their homes – one suitcase.

The Heart Mountain Relocation Center

The Japanese interment camp in Cody Wyoming was named for Heart Mountain Butte which you could see a few miles in the distance. The Heart Mountain Japanese Interment Camp has been reopened as a museum and gallery to remember this unfortunate period in American history. The Heart Mountain relocation center was functional from 1942 until 1945.

At its height, the Heart Mountain Japanese Internment Camp held over 10,000 Japanese Americans making it the third largest town in Wyoming. Approximately one-third of the occupants were Issei but the remainder were American citizens. All of the Heart Mountain inmates were of Japanese descent except one woman. She was a Caucasian who refused to part from her Japanese-American husband.

Although the Japanese internment camp in Wyoming was supposed to be open-gated, the state governor warned the racism of the locals would make it dangerous for the Japanese. The 46,000 acre camp was then surrounded by barbed wire, guard towers and searchlights.

Conditions at the Heart Mountain Japanese Interment Camp were basic. People were housed in barracks and even families were housed in single rooms.

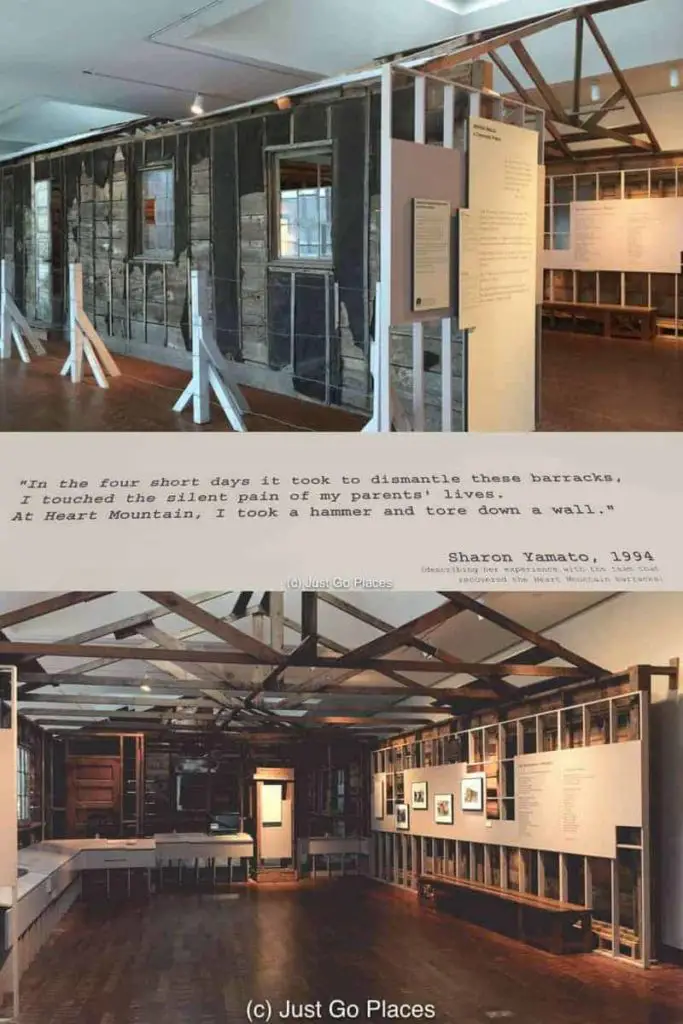

Although there was a stove in the room for heat, the Japanese-Americans living inside were used to a more temperate climate in California. The Heart Mountain relocation camp was located at an elevation of 4600 feet and the winter temperatures dipped to -30 degrees! Most of the Japanese Americans came from Los Angeles and Santa Clara (about 9000 people). They must have felt frozen in the Wyoming winters. The wind would have whipped through the buildings. The barracks had been hastily constructed, framed in timber and wrapped in black-tar paper.

Daily Life at the Heart Mountain Japanese Interment Camp

Family life was disrupted in a major way. For example, Japanese families have a tradition of respecting their elders. In the camps, however, the Issei had less rights than their American-born children because they were not American citizens. In another example, cafeteria-style eating meant that families no longer shared meals together.

Meals at the Heart Mountain Interment Camp were served in a cafeteria setting. Children were sent to schools that were created in the camp. Even a hospital was set up in the camp to take care of the internees needs.

One of the most distressing elements for the women was that the camps had communal bathrooms. With no doors for privacy, many women felt humiliated using the toilets.

The Drafting of Japanese-Americans at Internment Camps

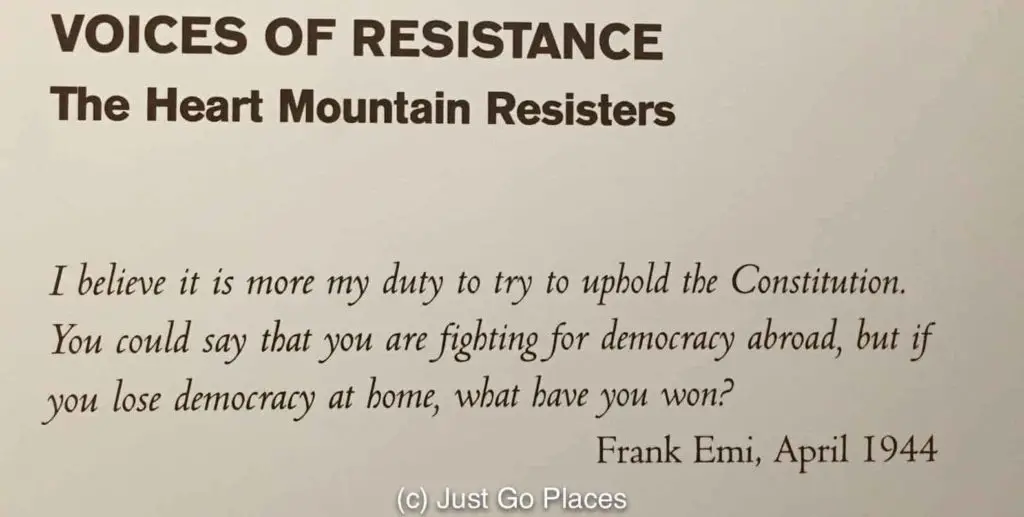

The American government extended the drafting of soldiers to the Japanese living in the camps even though their constitutional rights as Americans were being trampled. Needless to say, a group of men resisted the draft, were put on trial and imprisoned for disobedience. They were eventually pardoned by President Truman after the war ended. The 800 men who did join the war were part of the 442nd Regimental Combat Team. The 442nd became the most decorated military unit in US history. Of the soldiers recruited from Heart Mountain, 11 men were killed and 52 men were wounded. Two men received the Medal of Honor, the highest military award an American soldier can receive.

The Closing of the Heart Mountain Internment Camp

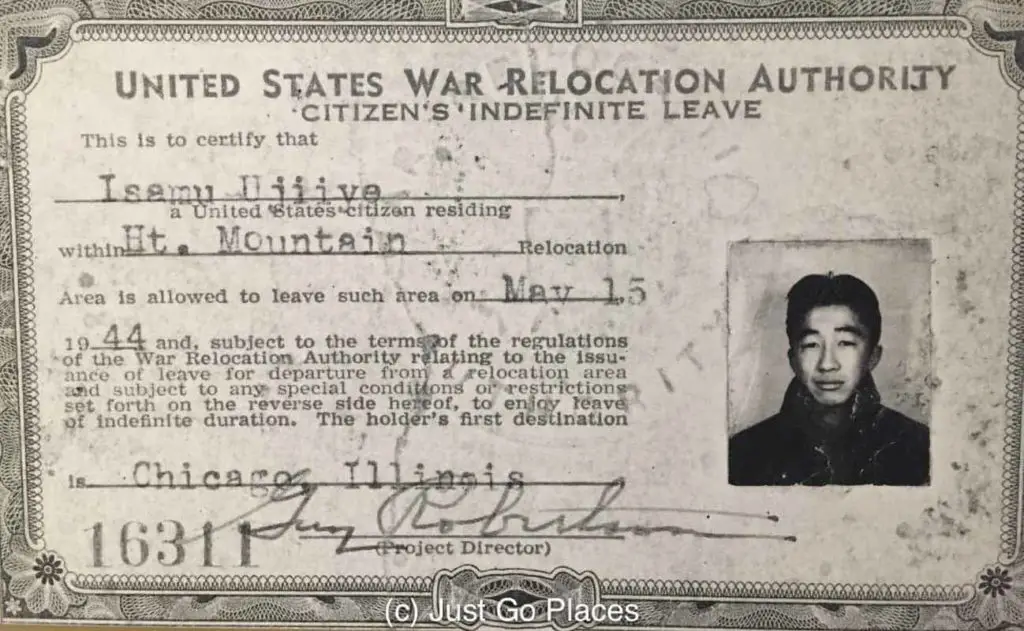

After the war ended, the Japanese Americans were told to disperse and given $25 and a one-way train ticket. They had lost all of their pre-war businesses and other assets so technically they had nowhere to go.

After their Heart Mountain internment at the end of World War II, the Japanese-Americans were told to scram.

The state of Wyoming passed laws that prevented the Japanese-Americans who had been subject to the Heart Mountain internment from staying in Wyoming. As part of the legacy of Heart Mountain, you can read the stories of people reintegrating back into mainstream American society. Those stories are equally heartbreaking with tales of suicide and despair. Who would believe that for some of the older Japanese-Americans the internment days were better than what these people faced reintegrating back into American society?

The Japanese American National Museum

If you are not in Wyoming, the Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles has great exhibits on the Japanese American internment during World War II. We saw one exhibit which was dedicated to the Japanese-American farm labourers. Many Japanese Americans had become seasonal farm labourers in the American heartland. The pay was better than at the internment camps. In addition, many of the Japanese Americans had experience working in agriculture.

One of the barracks from the Heart Mountain Japanese interment camp was dismantled and brought to the Museum in the 1990’s.

A Heart Mountain barrack is maintained at the Japanese American Museum in Los Angeles to remember the legacy of Heart Mountain.

Tips for Visiting Heart Mountain Interpretive Center:

The Heart Mountain Interpretative Center is located between the towns of Powell and Cody in Wyoming at the intersection of Highway 19a and Road 19. Look for a barn-like low building which blends into the landscape fairly close to the intersection. Adults pay an admission fee but children under the age of 12 are free. The centre is open daily during the summer but has limited open days during the winter.

I think perhaps my 8 year old children were a bit young to understand the injustice of what happened at Heart Mountain. Even though they knew about World War II because we had visited the D-Day beaches at Normandy, they didn’t quite grasp the horror of having someone’s life uprooted in a week.

My children thought it would be cool to live in a camp with all their friends but they did think it was unfair that they would have to lose all their possessions. Actor and activist, George Takei, 5 years old when he was sent to an internment camp in Arkansas, has spoken of how little he understood of the experience as a child.

Another activist and professor of law at the University of Hawaii, Mari Matsuda was a child when her family was sent to Heart Mountain internment camp. Her father volunteered for combat duty, and the family blamed the press, specifically the Hearst newspapers, for inciting war hysteria and racism.

The Heart Mountain Interpretative Center is a useful reminder of a bleak period in American history where American citizens were illegally detained and their civil rights trampled.

Practical Info To Know Before You Go

Check out the website for the Heart Mountain Interpretive Centre for opening times. You will definitely need to have your own car. We booked our rental car through Hertz of which we are Gold Card members. We stayed at the charming Chamberlin Inn in Cody, Wyoming. You may also want to consider the historic hotel, Buffalo Bill’s Irma Hotel where we had a nice dinner. Unfortunately, the Irma doesn’t allow children to stay at the hotel.

Further Reading:

[easyazon_link identifier=”0295974842″ locale=”US” tag=”jg20-20″]Years of Infamy[/easyazon_link] by Michi Weglen

[easyazon_link identifier=”0439569923″ locale=”US” tag=”jg20-20″]Dear Miss Breed[/easyazon_link] by Joanne Oppenheim

[easyazon_link identifier=”0345505344″ locale=”US” tag=”jg20-20″]Hotel on the Corner of Bitter and Sweet[/easyazon_link] by Jamie Ford

[easyazon_link identifier=”0142424374″ locale=”US” tag=”jg20-20″]A Diamond in the Desert[/easyazon_link] by Kathryn Fitzmaurice